Pulse Wave Velocity

Background

Main Project

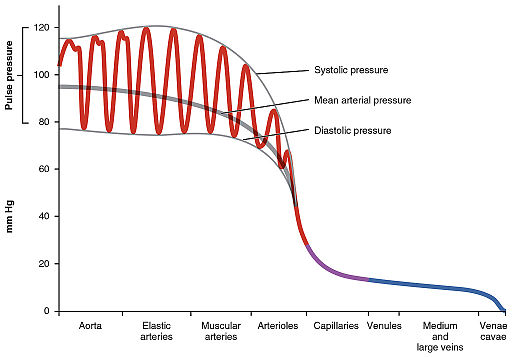

The effect of aging and cardiovascular disease plays an important role in progressive arterial stiffening that can be observed in older adults. When arteries become stiffer and less compliant, they cannot absorb pulsatile energy (systolic pressure) generated from the heart. This ultimately puts stress on smaller arteries (capillaries) that are not well suited for dissipating this energy. This can cause damage to peripheral organs, like the brain, kidneys, eyes, and heart. To measure arterial stiffness, one biomarker that has recently emerged is pulse wave velocity (PWV). PWV indirectly assesses vessel stiffness by measuring how fast blood pressure pulsations travel through larger arteries; stiffer arteries lead to faster traveling pressure waves. This method has become the gold-standard for non-invasively assessing arterial stiffness and has proven to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk and mortality. Because larger, more elastic arteries have a more active role in absorbing pulse pressures, PWV is most often measured in the aorta and its immediate branches.

OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Quick Side Note: A simple experiment to illustrate arterial PWV can be performed by placing one finger on your carotid artery near your neck and the other finger near your ankle where you can find a pulse. By feeling the pulse at both locations, you should notice a time delay in blood pulsations. The difference in distances between the heart and these locations, as well as the stiffness of your vessels, determines this time delay.

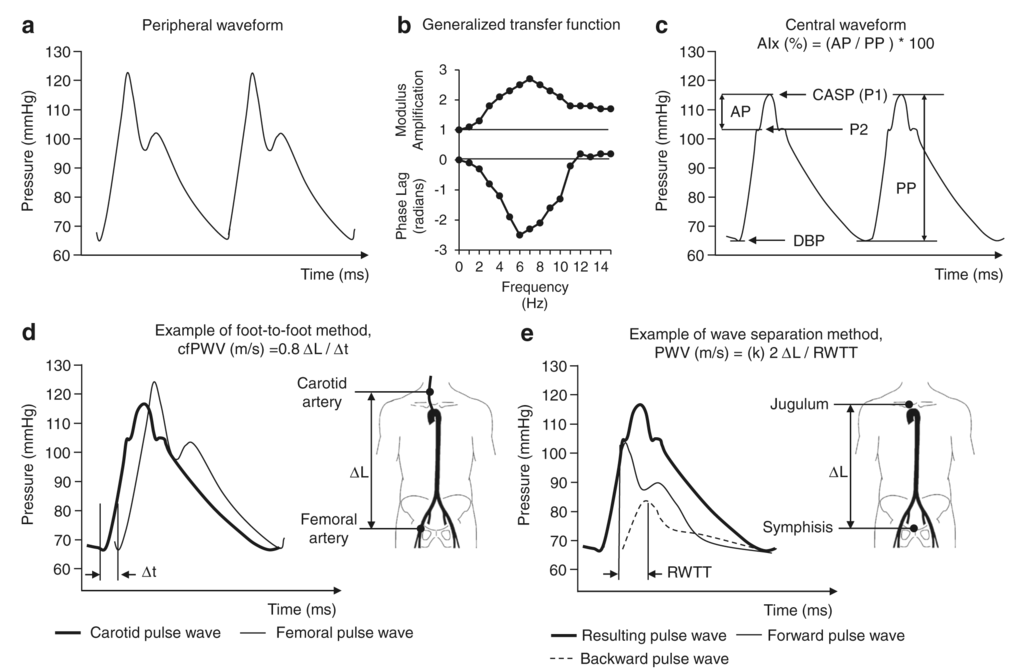

Typically, arterial/aortic PWV is measured by obtaining blood flow or pressure waveforms in the carotid and femoral arteries using tonometry, blood pressure cuffs, or ultrasound. Time delays (Δt) between these waveforms are calculated using mathematical methods. The faster the pulse pressure travels between these points, the shorter the time delay in the waveforms, which implies higher PWV, which again implies stiffer vessels. However, time delays are also a function of the distance, specifically, a vessel distance between the heart and each carotid/femoral measurement point (d_car/d_fem). To account for this, we calculate velocity based on the difference in distance (Δd = d_car/d_fem) between measurements (where aortic PWV = Δd/Δt). Distances are roughly estimated by measuring certain landmarks on the surface of the body using tape measures. While these approaches have been used successfully in many studies, the distance measurements are often prone to error because aorta morphology can vary from patient to patient.

Omboni S, Posokhov IN, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

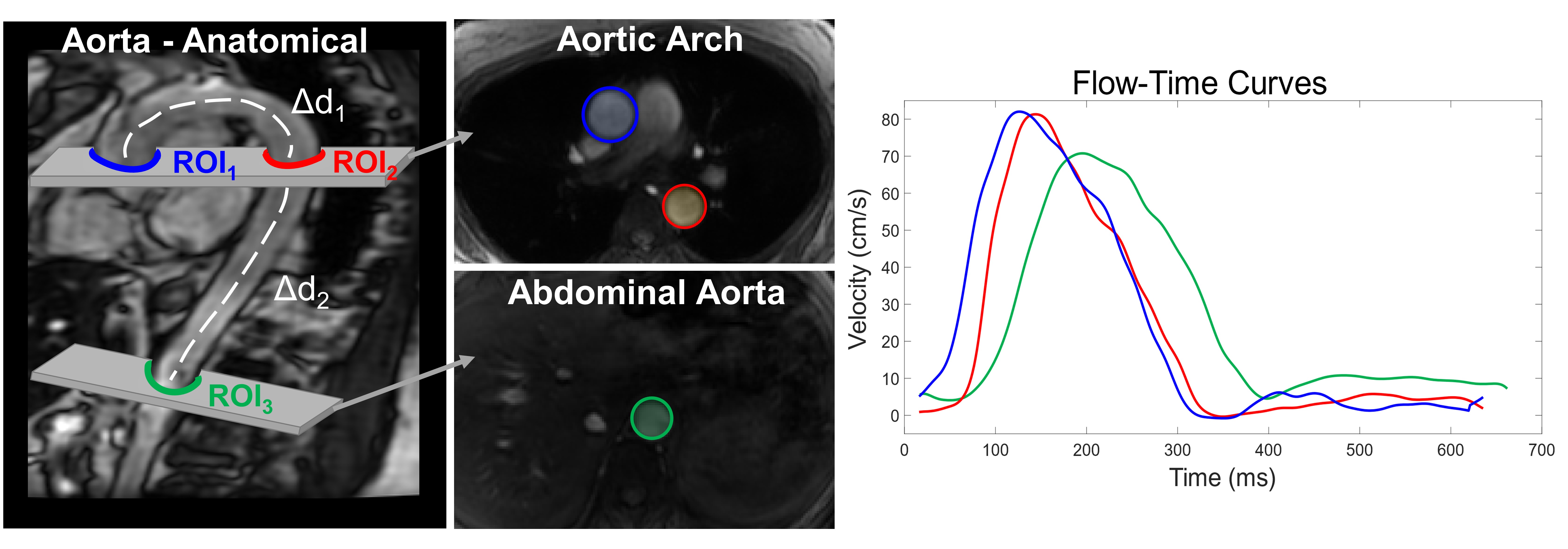

More recently, MRI has been used to evaluate aortic PWV with the use of cardiac-gated 2D phase contrast (2DPC) techniques. Phase contrast MRI allows us to measure blood velocities and flow waveforms over the cardiac cycle and has been used to obtain flow waveforms in the aorta, similar to tonometry and ultrasound techniques. However, unlike more traditional methods, MRI can directly obtain angiographic images of the aorta to compute aortic distances directly and are thus more accurately determined.

However, this approach is still challenging because it requires high temporal resolution to resolve sometimes subtle waveform time shifts. Higher temporal resolutions increase the overall scan time, which is especially problematic because these exams are usually done while the subject is holding their breath. This is because the aorta can move during respiration which can result in image artifacts. However, in some subjects such as elderly, diseased, or cognitively-impaired individuals, long (or even short) breath-holds may be difficult or impossible. Developing high temporal resolution, free-breathing PWV methodologies would thus be ideal.

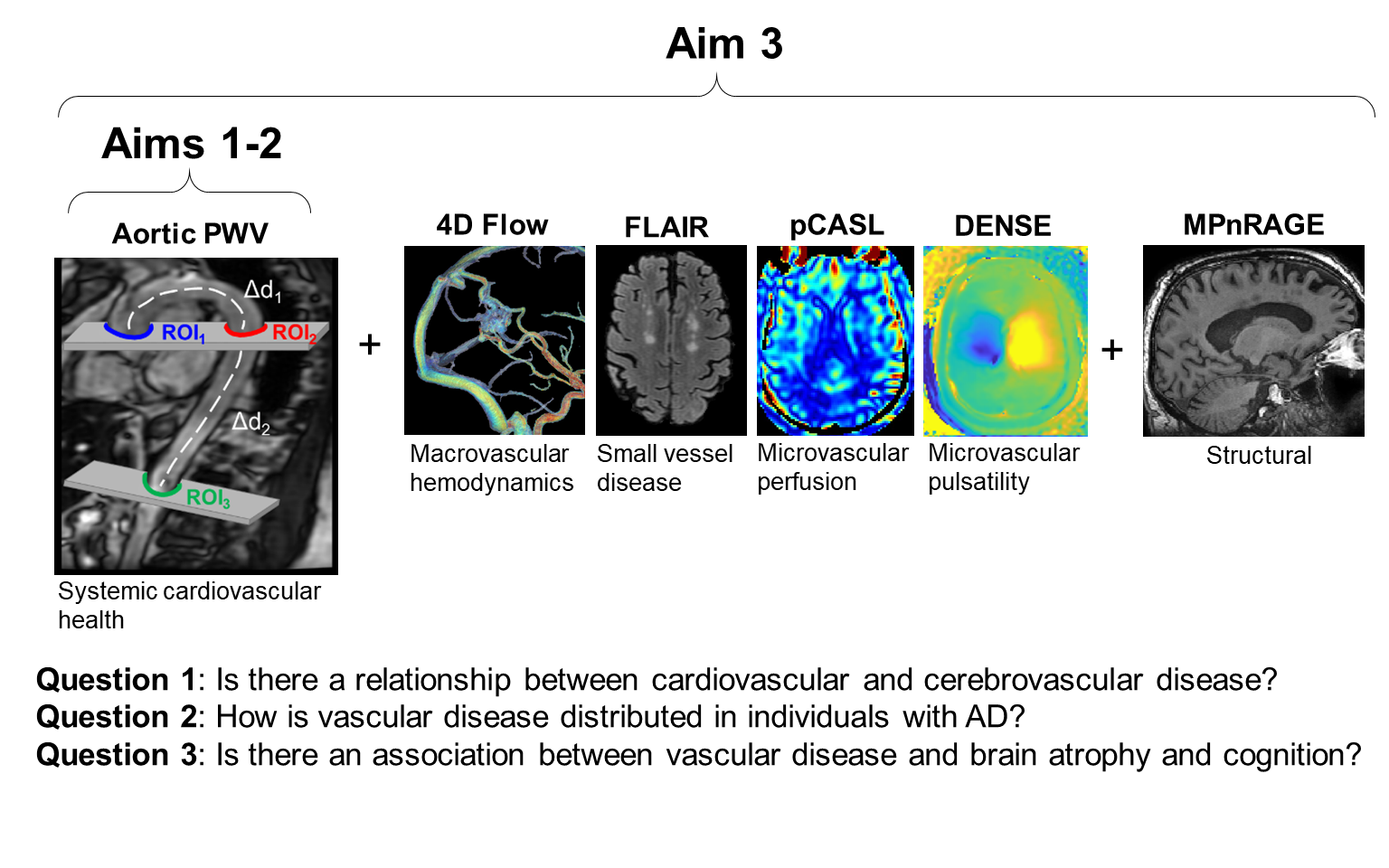

In March 2021, I was awarded a 2-year F31 fellowship through the NIA (F31AG071183). This research project is dedicated towards developing and validating a free-breathing, radial 2DPC simultaneous multi-slice (SMS) sequence with local low rank reconstructions to generate high temporal resolution images for accurate aortic PWV measurements. In addition, a robust post-processing analysis platform has been developed for automated, and repeatable PWV measures to enable analysis in large cohort studies, several of which are currently underway at the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). The new imaging protocol will be used in a pilot study consisting of an AD cohort and an age- and sex-matched control group to collectively assess systemic cardiovascular health, macrovascular, and microvascular dynamics in the brain for the first time.

Separately from the above project, we currently are involved in (and helped establish the MRI protocol for) the ongoing NIH-funded project Longitudinal Impact of Fitness and Exercise (LIFE) study led by Dr. Ozioma Okonkwo. This study is designed to assess the impact of physical activity and aerobic fitness on biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in midlife. A subaim of this project is to capture an individual’s global cardiovascular state by measuring PWV in the aorta. To do this, we perform: anatomical images for obtaining aortic distances, 2D cine bSSFP images to measure time-resolved aortic areas (PWV-QA method, see section below), Cartesian 2DPC (standard PWV method), and radial 2DPC (new PWV method).

- Free-breathing Anatomical 2D bSSFP

- Sagittal slices (higher resolution)

- Coronal slices

- Axial slices

- Breath-hold 2D Cine bSSFP (~0:12 each, for PWV-QA measures)

- Axial slice in aortic arch (transects both ascending and descending aorta)

- Axial slice in abdominal aorta

- Breath-hold Cartesian 2DPC (~0:12 each)

- Axial slice in aortic arch

- Axial slice in abdominal aorta

- Breath-hold Radial 2DPC (~2:00 each)

- Axial slice in aortic arch

- Axial slice in abdominal aorta

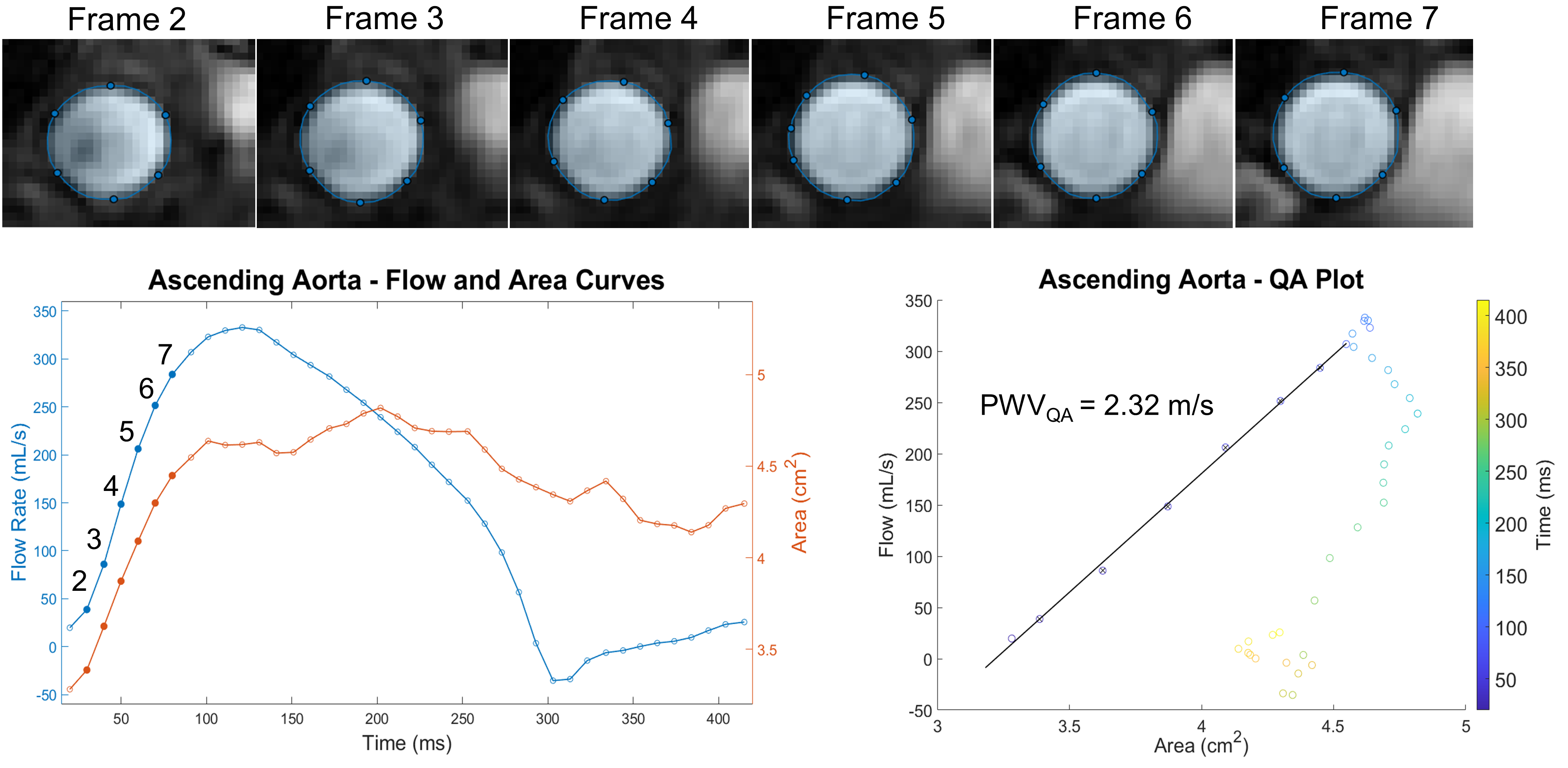

PWV-QA Method

We have also looked into alternative approaches to estimate pulse wave velocity. One interesting method, termed the QA method presented by Vulliemoz et al, evaluates the change in vessel area changes in early systolic flow to estimate vessel stiffness (via the Bramwell-Hill equation) and thus PWV. Specifically, a flow-area plot is created using flow and area measurements obtained during the systolic phases (frames) of the cardiac cycle. A line is fit to this portion of the curve, where both flow and area are increasing, in which the slope is equivalent to the local aortic PWV. This method assumes no wave reflection, which suggests that the PWV-QA should be restricted to the proximal portion of the aorta where no wave reflections exist. Furthermore, since this method is sensitive to only systolic time frames, a representative sampling of points is required for accurate linear regression which requires very high temporal resolution (and is the subject of our 2022 ISMRM abstract). Additionally, in the method presented Vulliemoz, 2DPC magnitude images were segmented for area measurements. However, these images can be prone to inflow-effect, which may adversely affect the ability to accurately segment the aorta. In our ISMRM abstract, we used cine bSSFP images to obtain area measures, which showed better delineation of the aorta boundary.

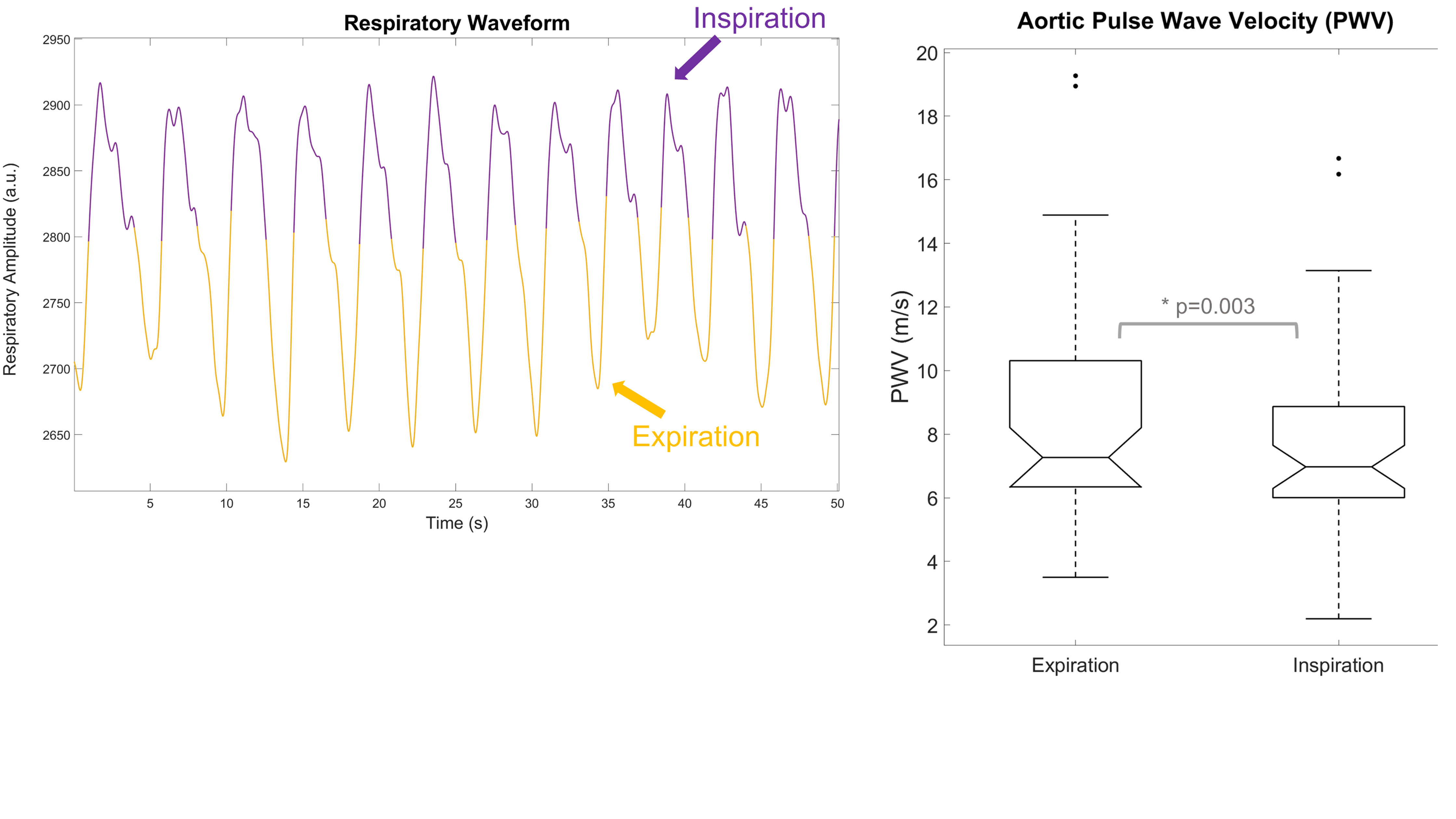

Effect of Respiration on PWV

In a recent abstract submitted to ISMRM, we looked to see if there was an effect of respiration on PWV measurements. Interestingly, there has not been published work on the effect of respiration on PWV, aside from a short abstract looking at the effect of respiration on tonometry-based carotid-femoral PWV. For our study, we performed retrospective respiratory gating on free-breathing radial 2DPC scans to obtain 2 separate datasets: one gated on expiration, another gated on inspiration. PWV analysis was performed as usual for both inspiration-gated and expiration-gated datasets. We found that PWV measurements taken from inspiration were on average 10% lower relative to expiration. Our results were consistent with the findings from the pressure tonometry study. The physiological mechanisms for this are unclear but may be due to intrathoracic/arterial pressure changes, blood flow rate changes, or short-term hypoxia affecting vascular tone.

Collaborations:

Ozioma Okonkwo Lab, Waisman Brain Imaging

Code

- 2DPC PWV - Cine Reconstruction (Matlab)

- 2DPC PWV - Real-time Reconstruction (Matlab)

- 2DPC PWV - QA Method (Matlab)

Abstracts

Oral Presentation

- Roberts, G. S., Johnson, K. M., Rivera-Rivera, L. A., Kecskemeti, S. R., Okonkwo, O. C., Eisenmenger, L. B., & Wieben, O. Free-Breathing Radial 2D Phase Contrast MRI for Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Measurements in Healthy Older Adults. Society for Magnetic Resonance Angiography (SMRA) 32nd Annual International Conference; 2020 September 18. Download

Poster Presentation

- Roberts, G. S., Bernhardt, Z. S., Lose, S., Pandos, A., Johnson, K. M., Eisenmenger, L. B., Okonkwo, O., & Wieben, O. Effects of Respiration on Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity using Retrospective Respiratory Gated Radial 2D Phase Contrast MRI. Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB & SMRT 31st Annual Meeting. 2022 May 7. Download

- Naren, T., Roberts, G. S., & Wieben, O. Effect of Temporal Resolution on Flow-Area Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Measures Using Phase Contrast and Balanced SSFP MRI: A Preliminary Study. Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB & SMRT 31st Annual Meeting. 2022 May 7.

- Roberts, G. S., Johnson, K. M., Kecskemeti, S. R., Okonkwo, O., Lose, S., Eisenmenger, L. B., & Wieben, O. Feasibility of a Free-Breathing 2D Phase Contrast MRI for Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Measurements. 2020 ISMRM & SMRT Virtual Conference & Exhibition; 2020 August 08. Download

Awards

- March 2021 - I was awarded the Ruth L. Kirschtein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral F31 Fellowhsip for this work (F31AG071183).

- June 2022 - Tarun Naren was awarded T-2nd place for best abstract in MR Flow and Motion ISMRM Study Group on his work related to the PWV-QA method.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *